A triune system of regulation, safety and connection

We live in a zeitgeist described as VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous), with prolonged stress and trauma as common denominators resulting in chronic health and relational conditions becoming more prevalent. This led to the inclusion of both Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and its chronic version, Complex PTSD (C-PTSD), in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11, 2022).

This recent inclusion is a significant landmark for global health, as PTSD has been included in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) since 1980. Whilst a singular accident or natural disaster often causes PTSD, C-PTSD arises from prolonged, multiple episodes of relational and emotional stress, often involving betrayal of trust within familial, societal, and professional environments.

C-PTSD has become the “disorder” of our time, manifesting in many chronic relational, psychological, and physical conditions/symptoms. The additional self-regulatory symptoms of C-PTSD often overlap with traits found in neurodiverse individuals, such as those on the autism spectrum or with ADHD.

At Neuroceptive Learning, we acknowledge the link between events leading to C-PTSD and nervous system dysregulation and the similarities in symptoms experienced.

Whilst we cannot escape our VUCA/BANI world, by supporting our nervous system regulation, we can experience our immediate environment as “psychologically safe.” Psychological safety refers to our sense of inclusion and ability to speak up, contribute, and challenge within our social, work, and other groups. It influences our ontology (who we are), performance, possibilities, physical and mental health, and well-being.

Our nervous system holds the answer to addressing chronic conditions

The importance of our nervous system cannot be overstated. Across various disciplines, from complementary medicine and ancient Eastern traditions to modern neuroscience, there is a deep recognition that our nervous system is central to our overall well-being. Practices such as osteopathy, craniosacral therapy, naturopathy, yoga, and traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine all emphasise the flow of life energy, which can be understood as a reference to the information flow within our nervous system.

For instance, osteopath Randolph Stone developed Polarity Therapy, which integrates Western medicine and Eastern traditions. He referred to our energy anatomy as the “wireless” system and our nervous system as the “wired-in” system. Similarly, osteopath James Jealous posited that 80% of all physical, relational, and psychological conditions can be traced back to a dysregulated nervous system.

Similarly, Dr Jean Ayers of Sensory processing theory and Dr Mosché Feldenkrais used the principles of Neuroplasticity and how our nervous system functions in their awareness through movement and sensory integration methods to improve emotional regulation, executive and physical functioning, well-being, learning and performance. Jean Ayres defined Sensory Integration as “the neurological process that organises sensation from one’s own body and the environment and makes it possible to use the body effectively within the environment.”

In their seminal work, The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding (1992), Maturana and Varela emphasised that “the only world we can know is the world our nervous system allows us to observe. This is a world of actuality and possibility.” Their insights underscore the fundamental role of the nervous system in shaping our perception of reality, influencing everything from our sense of safety to our capacity for regulation, connection and learning.

In the last 30 years, Stephen Porges’s Polyvagal Theory (PVT) has significantly expanded our traditional understanding of the nervous system. PVT builds on the ideas of Maturana and Varela and supports Jean Ayers’s sensory processing theory. The PVT describes a nervous system that phylogenetically evolved to allow precisely what is now broken in our stressful VUCA world: societal living, trust, and co-regulation with others – psychological safety.

PVT has informed the work of many trauma practitioners, such as Bessel van der Kolk, Peter Levine, Larry Heller, Pat Ogden, Kathy Kain, Deb Dana, Gabor Maté, Anna Chitty, and Stanley Rosenberg, to name but a few. It is starting to influence other domains, notably our educational system. However, its potential to provide options to address chronic conditions and to increase our overall quality of life is still under-utilised. By being informed about how our nervous system influences our potential, health and well-being, leaders can create environments for us to thrive in our VUCA world. As Bessel van der Kolk eloquently states, much of what we consider “disorders” is more accurately seen as breakdowns in relationships and social structures.

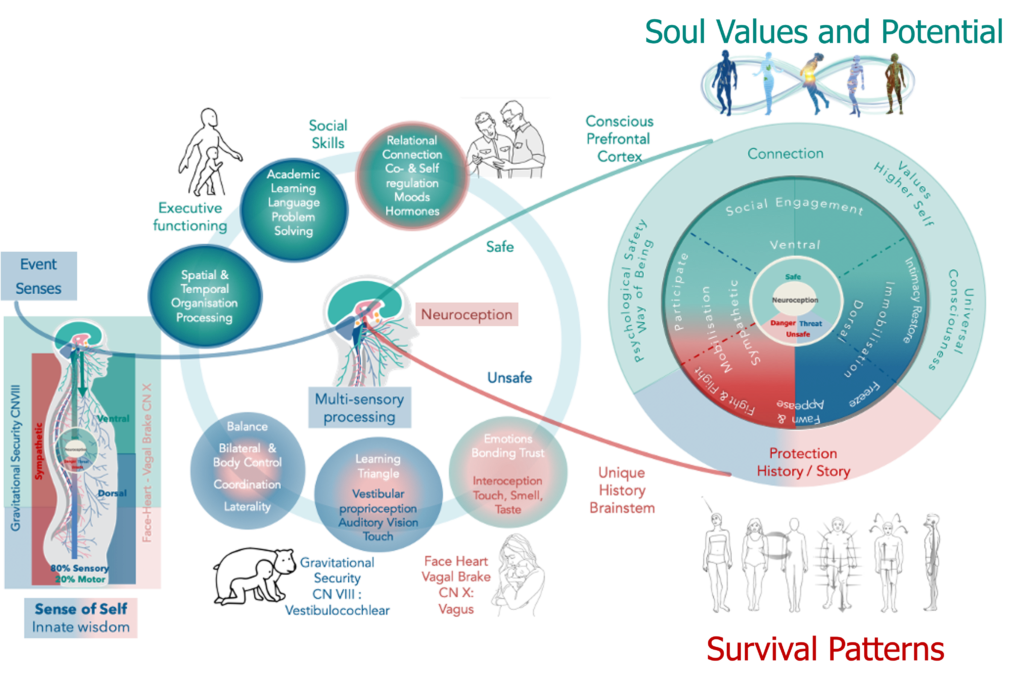

PVT follows how our nervous system naturally functions. It expands and sheds a different light on critical elements of our traditional understanding. Combined with sensory processing theory, it provides a far better unified Phylogenetic framework of our nervous system’s functioning and humanness to influence our decisions on our health and well-being. It is an indication of our potential given an optimal nervous system. Our Ontogeny (containing our stress/ traumatic events) is how our nervous system enfolds against this potential – it can either promote and support or hinder our Ontology (our way of doing, being, becoming & belonging).

PVT enhanced Phylogenetic Framework

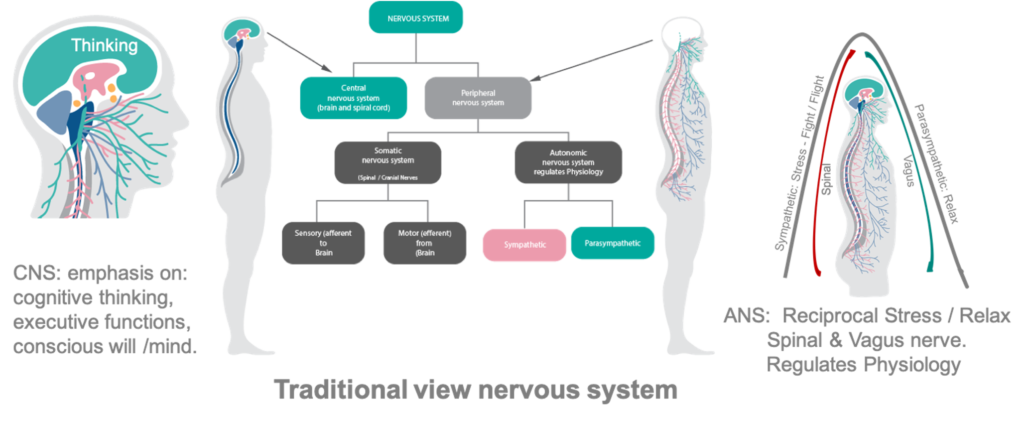

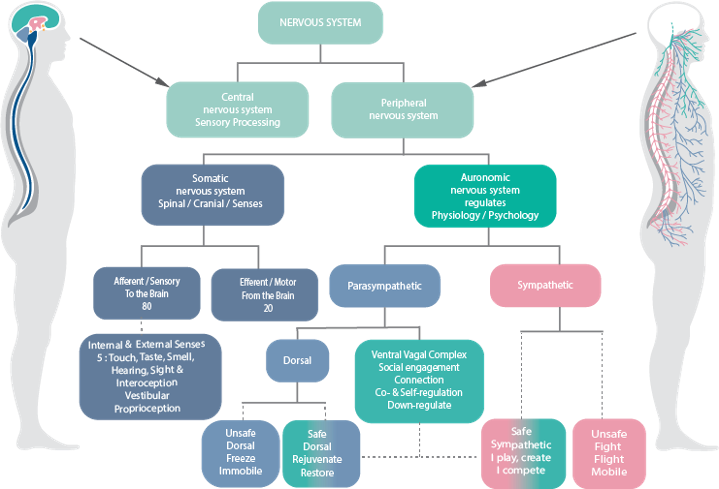

Our traditional understanding of the nervous system is that it is divided into the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS), which includes the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the somatic nervous system. However, this division often overlooks the interconnectedness of these systems, and the PVT explains a unified nervous system functioning as a whole.

The following highlights where the PVT and sensory integration theory expand upon traditional views:

- Traditionally, the somatic nervous system links the CNS to skeletal muscles under conscious control and sensory receptors in the skin. The somatic nervous system brings sensory (afferent) information from the periphery to the CNS, and the CNS sends motor (efferent) responses back.

PVT: While we are most aware of our five external senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell), PVT, recent trauma practitioners and research have highlighted the critical role of internal senses – such as interoception, proprioception, and the vestibular sense – in our overall well-being. PVT also highlights the importance of the 12 cranial nerves, especially the Vagus nerve CN X, and spinal nerves in conveying bidirectional sensory-motor information from our environment and bodies. Eighty per cent of the vagus nerve fibres are afferent (from body to brain), and only 20% are motor, indicating the importance of sensory input from our internal senses.

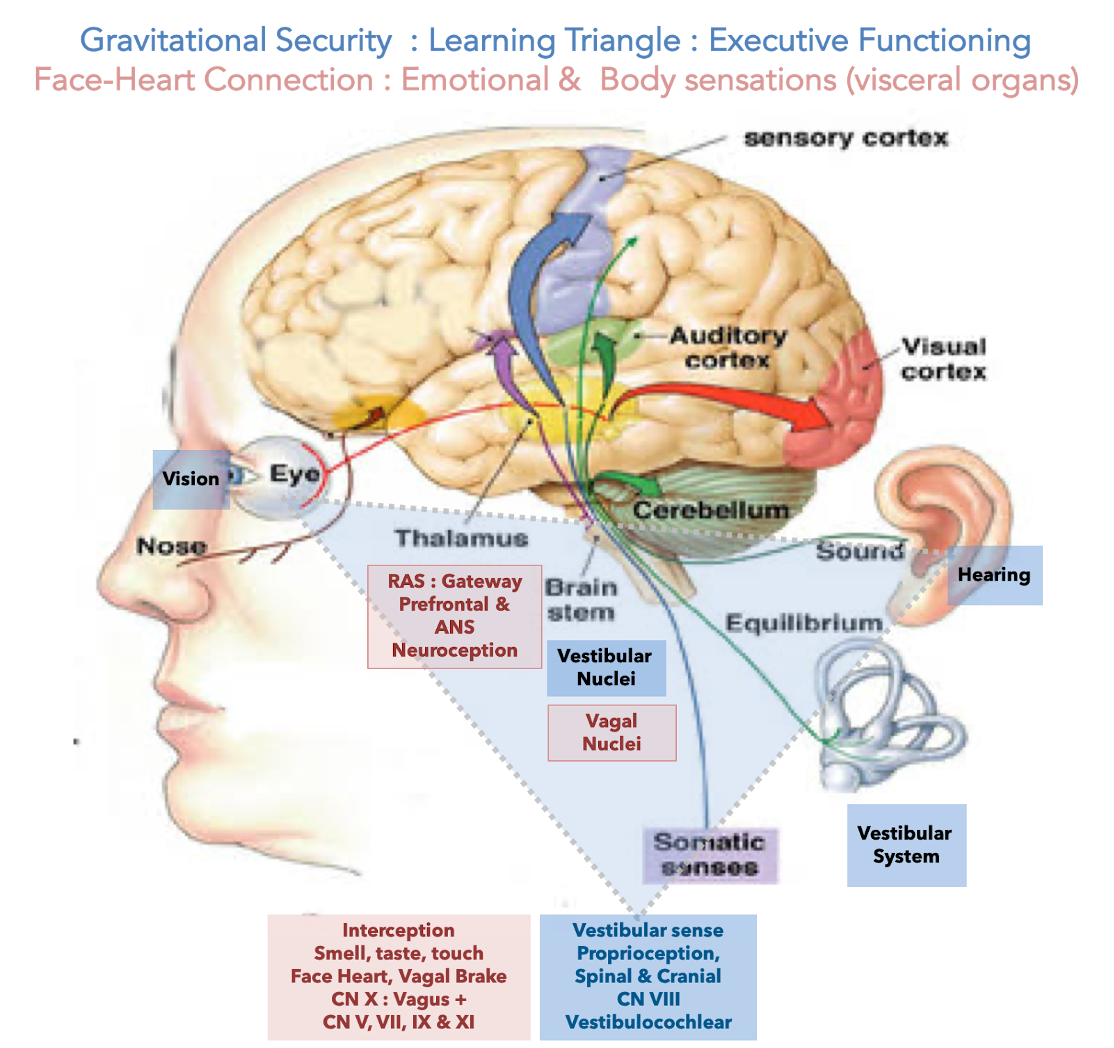

Similarly, the Sensory processing theory explains the role of our Vestibulocochlear nerve CN VIII combined with our cerebellum, in integrating all our senses to ensure executive functioning within the gravitational field.

The vestibular and vagal nuclei in the brainstem act as gateways in the bi-directional communication between the body and the brain.

- Traditionally: Our autonomic nervous system (ANS) operates largely outside of conscious awareness. It regulates our physiological state to ensure survival through stress (sympathetic activation facilitated by spinal nerves) and relaxation (parasympathetic regulation facilitated by the vagus nerve – cranial nerve X). This dualistic reciprocal ANS keeps us in homeostasis, maintaining optimal physical health. In danger, however, this regulation is compromised, shifting resources from health maintenance to protection.

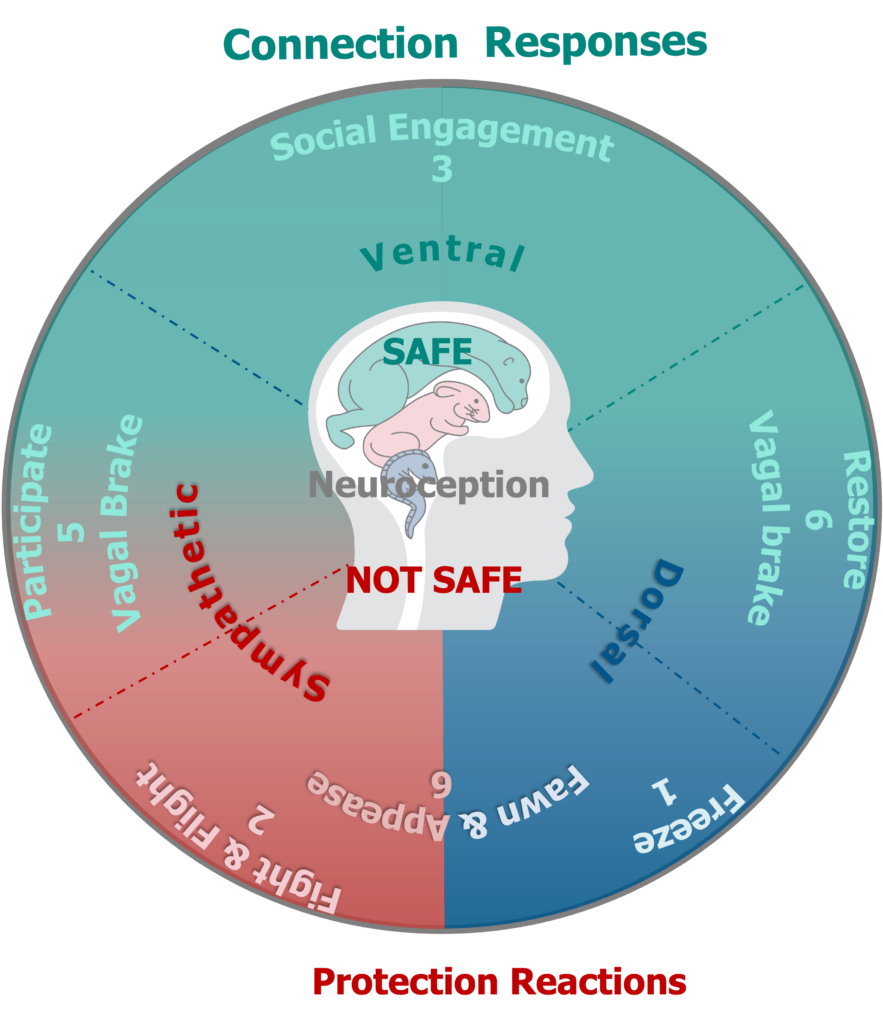

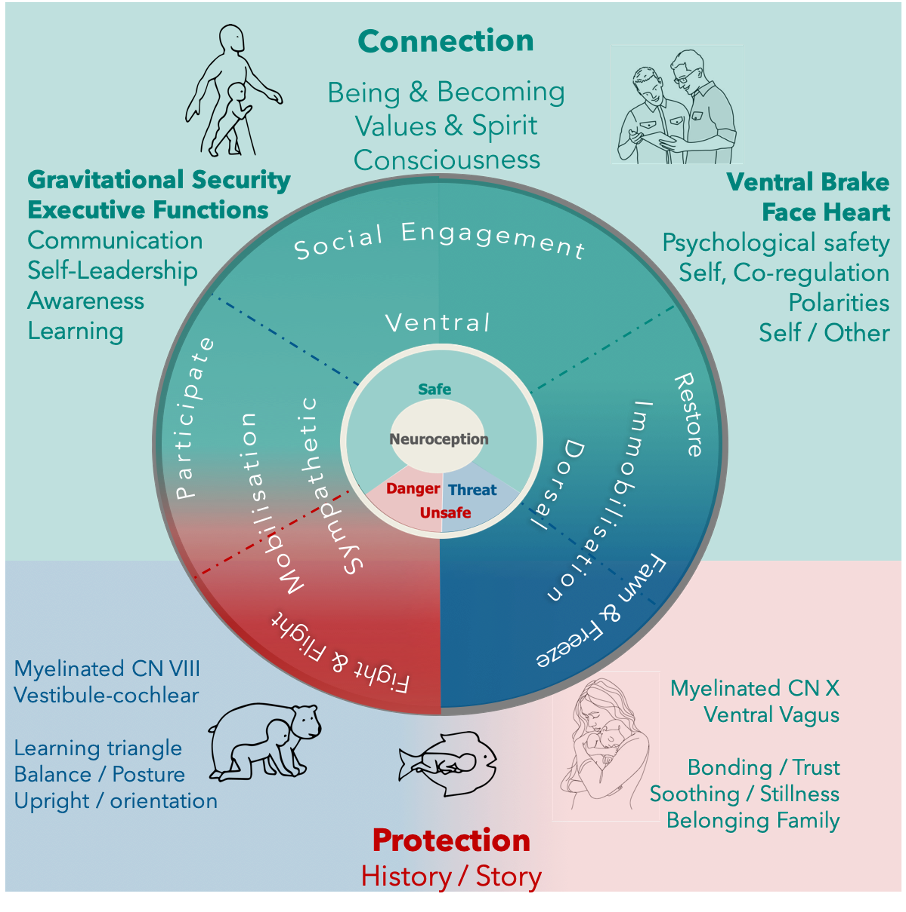

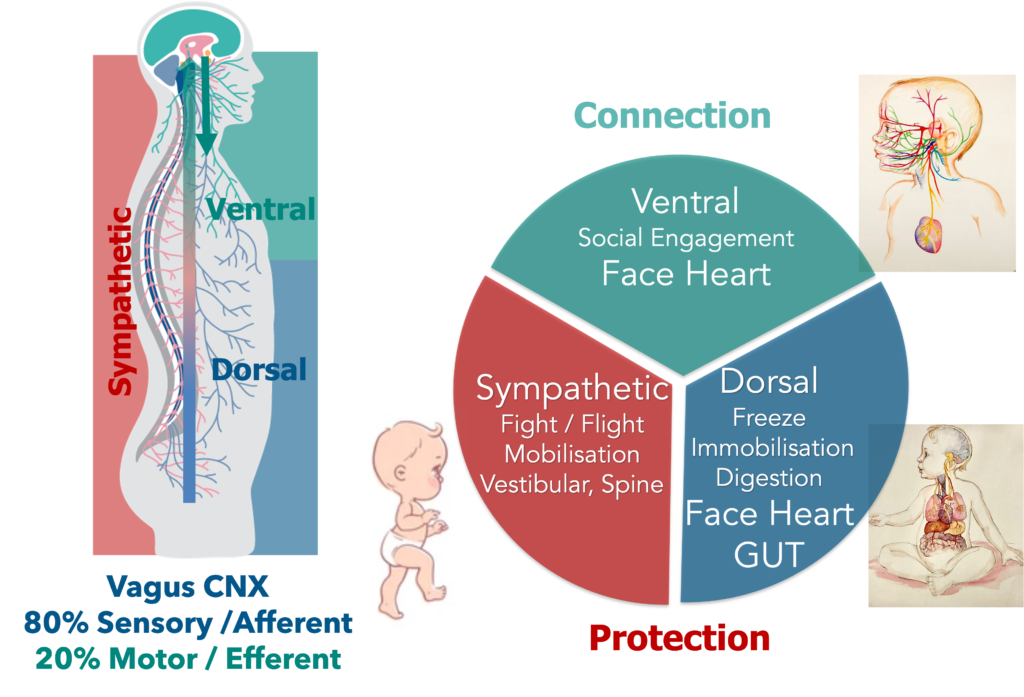

PVT explains that the ANS has evolved to allow societal living. Therefore, it regulates connection responses (to live among each other) and protection reactions (for our survival), influencing our physical and psychological health and well-being.

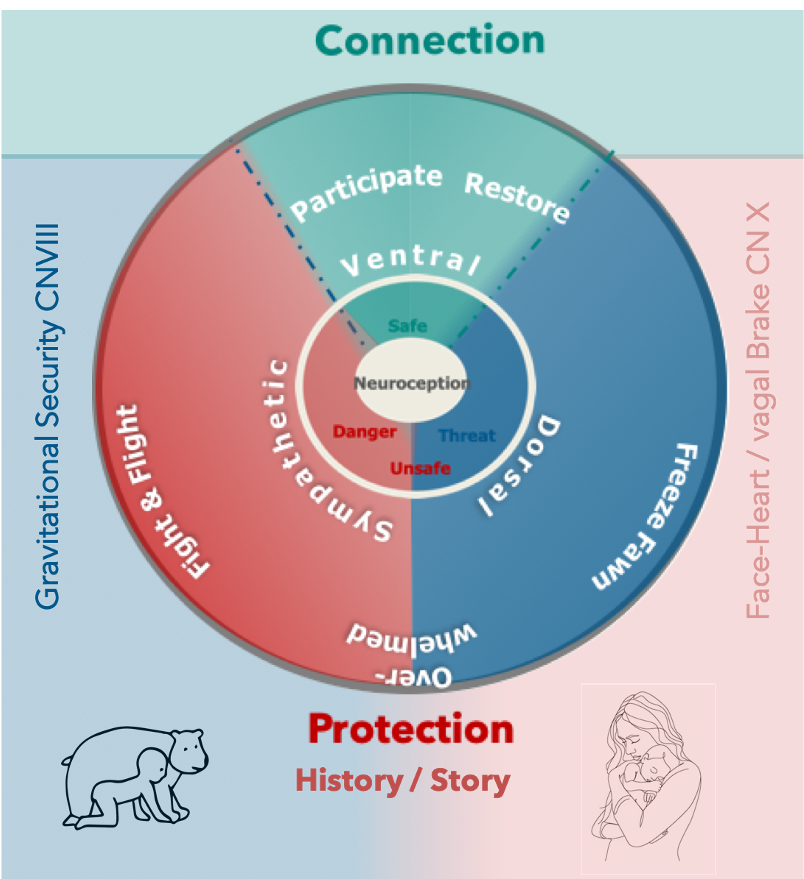

PVT explains the difference in the functionality of our dorsal and ventral vagal nerve branches and how our subconscious evaluation of safety, which Porges calls neuroception, is crucial to a well-regulated nervous system. Therefore, we have a triune, more nuanced ANS facilitated primarily through our ventral vagus nerve (Connection: face-heart, vagal brake), spinal nerves (Protection: sympathetic fight and flight), and dorsal vagus nerve (Protection: freeze). Neuroception is crucial to its functioning.

- CNS and the brain. According to MacLean’s triune brain model, the brain receives and processes sensory information from the PNS at the brainstem, integrates it with our emotional history in the limbic system, evaluates for safety before activating the ANS, and coordinates our response and executive functioning through the prefrontal cortex.

PVT makes us aware that our emotional history is not only embedded in “memory” areas in our limbic system but is more complex. It is also embodied in our physical body and embedded in our senses, influencing their functioning, ANS regulation, and CNS executive functioning.

- Bottom-up and top-down: Our nervous system functions from the bottom up—from the body to the brain and within the brain, from the brainstem to the prefrontal cortex.

Despite this, much of our medical, educational, and societal structures have prioritised top-down approaches, emphasising cognitive functions and decision-making (“I think, therefore I am”) over sensory processing.

The PVT supports Jean Ayers’s observation that 80% of the brain’s activities are sensory processing. Both make us aware of the bottom-up functioning of our nervous system, where sensory information and neuroception play a crucial role in our regulation, behaviour, and ontology. Changing Descartes to: “I sense, I neurocept, I regulate, I think, therefore I am.”

Our Ontogeny, our history of stressful and traumatic events leading to PTDS and C-PTDS, are embodied and embedded in our sensory information, impacting our neuroception and nervous system’s functioning and our potential.

To limit the impact of our Ontogeny on our potential, we need approaches/structures that are both top-down and bottom-up and in line with the natural functioning of our nervous system.

PVT: Our Evolved Vagus Nerve (Cranial Nerve X)

PVT reveals an evolved mammalian autonomic nervous system (ANS) that regulates not only for survival and protection but also for connection, enabling social engagement and societal living. To facilitate this, the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) evolved into two major pathways with entirely different functionalities: older unmyelinated dorsal pathways (for protective freeze regulation) and newer myelinated ventral vagal pathways (connection regulation – social engagement).

The older unmyelinated dorsal vagal pathways travel primarily to our organs below the diaphragm and originate in the dorsal motor nucleus in the brainstem. With a neuroception evaluation of safety, they support homeostatic functions and ANS regulation of our digestive system and organs below the diaphragm – our face-heart-gut connection.

However, if our neuroception detects extreme danger, our dorsal vagal pathways instantaneously transform into instinct-driven reactive immobilisation protection reactive regulation of freeze or shutdown and dissociative behaviours. This can be an instantaneous shutdown reaction to a threat but could also occur after prolonged continuous sympathetic mobilisation reactive regulation of fight and flight when our protective reactions move into immobilisation freeze reactions.

The newer myelinated ventral pathways travel and regulate primarily organs above the diaphragm. Myelin is a fatty substance surrounding the fibre, enabling the signal to be transmitted with greater specificity and speed. It functions from an area in the brainstem called the nucleus ambiguus. From this area, special visceral efferent pathways of cranial nerves (CN V, VII, IX, X, and XI) control the striated muscles of the face and head. Combined, they form what Porges calls our “face-heart connection.”

- CN V: The trigeminal nerve contributes to facial, head, and mouth sensations. It allows us to bite and chew.

- CN VII: The facial nerve helps us control most facial muscles that allow us to express emotion when talking to others. The facial and trigeminal nerves also have branches that reach the middle ear and regulate the smallest muscles in our entire body. These tiny muscles help us dampen background sounds to hear speech better.

- CN IX: The glossopharyngeal nerve is involved with our ability to taste, salivate, and swallow. Along with the vagus, it regulates the motor functions of the pharynx and larynx that allow us to speak.

- CN X: The vagus nerve is the wandering nerve in our body; its name comes from “vagabond,” which means wanderer. It is a cranial nerve that travels down into our bodies and provides a bidirectional “information superhighway” connecting every organ in the body with our brainstem—most importantly our gut (dorsal), heart, and face (emotions) with our mind (thinking). The vagus nerve is 80% sensory—from the body to the brain—and only 20% motor, highlighting the importance of body sensations (interoception sense) in influencing our ANS regulation and overall well-being.

- CN XI: The accessory nerve is involved with our ability to control various neck and head muscles, including those that allow us to shrug physically and those that enable us to vocalise through our larynx and pharynx.

The face-heart connection enables mirroring of facial expressions, nuanced social interactions, and prosody of our voices and body language. It promotes social engagement and co-regulation through our ANS, allowing us to interpret somebody else’s autonomic state and broadcast it to others. It will enable us to trust and bond with our primary caregivers as infants and later to trust, connect, and co-regulate with others. In the process, we learn social skills and self-regulation.

The face-heart connection expands our reciprocal ANS to a triune ANS regulation system of:

- Connection: Ventral (Social Engagement: Face-Heart Connection)

- Protection: Sympathetic (Mobilisation: Fight & Flight)

- Protection: Dorsal (Immobilisation: Freeze)

With a well-developed face-heart connection, when our neuroception evaluates a situation as unsafe, we will first use our social engagement to protect ourselves through communication and negotiation. If this does not work, we will protect ourselves through mobilisation of fight and flight and, as a last resort, through immobilisation – freeze reactions. In extreme danger, our dorsal vagal freeze reaction can immediately spontaneously activate.

PVT also describe the Vagal Brake, as a function of the myelinated ventral vagal pathways to “down-regulate” protection reactions to Connection Responses. These pathways can keep your heart rate calmer under stress and sympathetic mobilisation reactions (fight and flight) or increase it when you want to activate out of immobilisation reactions (freeze). Thus, they function as an active vagal brake in which inhibition and recovery of the vagal tone to the heart can rapidly mobilise or calm an individual.

Doing this provides the protective sympathetic and dorsal reactions with access to the prefrontal cortex and more pro-connection responses. It changes the sympathetic mobilisation reactions to participation and play responses and the dorsal immobilisation reactions to restore, rejuvenate, and intimacy responses.

Nuanced Triune System of Regulation governed by Neuroception

However, the vagal brake is facilitated by a neuroception evaluation of safety, which expands our triune ANS system of regulation to a more nuanced ANS system of different states of regulation, as shown in the diagram and discussed below:

Protection Circuits (Neuroception = not safe, our ontogenetic history is in charge)

Dorsal Vagal (oldest): Associated with immobilisation and shutdown regulation. In this state, the body conserves energy by slowing heart rate, lowering blood pressure, and reducing bodily functions. It may be accompanied by feelings of dissociation, disconnection, numbness, a mood of resignation, and an “I give up” message. The behavioural response is Freeze: unable to move or act against a threat.

The prevailing mood is described as resignation: “I give up, I cannot get out of here.”

Sympathetic: Associated with mobilisation and fight-or-flight reactions. In this state, the body prepares for action: heart rate increases, alertness is heightened, and stress hormones are released. It may be accompanied by anger, resentment, and a message of “Why me and how dare you!” Behavioural responses include:

- Fight: Facing any perceived threat aggressively.

- Flight: Running away from danger.

The mood is described as resentment: “Why is this happening? Why me? This cannot be happening.”

Fawning is a hybrid Protection circuit of the sympathetic fight, flight, and dorsal freeze involving a mood of confusion and anxiety and pragmatic behaviours: trying to please through compliance to avoid conflict and diminish aggression and threat.

Appeasement is a hybrid Protection circuit involving sympathetic activation, dorsal freeze, and, to a certain extent, social engagement, characterised by the behaviour of attempting to convince the perpetrator’s nervous system that you are on their side.

Connection Circuits (Neuroception = safe combined with Vagal Brake)

Social Engagement / Ventral Vagal (the newest state): The ventral vagal nerve, along with cranial nerves CN V, VII, IX, and XI, forms our face-heart connection, essential for bonding, co-regulation, and developing relationships. It fosters social engagement, communication (talking and listening), empathy, and moods of gratitude, curiosity, and wonder. We protect ourselves by using communication and negotiation. It can act as a “ventral brake”, down-regulating the sympathetic and dorsal protective circuits to promote connection-regulated responses.

Play: Safe Sympathetic (Sympathetic + Vagal Brake): A state where the dynamic mobilising qualities of the sympathetic circuit are used for participation. We use “healthy” aggression to express ourselves, set boundaries, compete, and contribute, accompanied by a mood of ambition, achievement, and healthy competition.

Restore/Intimacy: Safe Dorsal (Dorsal + Vagal Brake): A state where the restorative qualities of the dorsal circuit are used to foster safety, intimacy, rejuvenation, deep relaxation, and sleep, with a mood of acceptance and contentment.

Neuroception Safety Unlocks Connections and Regulation

Neuroception influences whether our nervous system responds with connection responses – incorporating input from our cognition to promote health and well-being – or with protection reactions – prioritises survival but limits cognitive input and compromises our health and well-being.

A robust, well-developed nervous system mainly has a neuroception evaluation of safety and regulated connection responses. Only in real danger should neuroception be unsafe with protection reactions, returning to safety and connection responses once the danger has passed. owever, if our neuroception becomes compromised and biased towards unsafe evaluation and prolonged protective reactions, we will struggle to return to connection-regulated responses. This is when our nervous system becomes dysregulated. A dysregulated nervous system leads to symptoms and chronic conditions similar to those experienced in C-PTSD and PTSD and prevents us from realising our potential.

We all receive the same sensory input, but our responses depend on our neuroception evaluation.

Our neuroception is shaped by our embodied ontogeny and conveyed via afferent and efferent neural pathways, mainly to the brainstem for sensory processing. Our ontogeny is also embedded and influences the functioning of our neuro-building blocks of face-heart connection, vagal brake, face-heart-gut and gravitational security.

PVT emphasises the building blocks of face-heart-gut, face-heart connection, and vagal brake. These are mostly facilitated through different attributes of the Vagus nerve complex cranial nerves (CN V, VII, IX, X, XI), and the internal sense of interoception combined with all our other senses.

It also describes the sympathetic circuits of our ANS, which are primarily facilitated by spinal nerves and the Cranial Nerves (CN II, III, IV, VI & VIII), notably CN VIII combined with cerebellum structures and our vestibular, proprioception, touch, vision and auditory senses. However, Jane Ayers’ sensory processing theory further expands upon this with the concepts of Gravitational Security and the Learning Triangle.

Sensory Processing Theory: Vestibular system (Cranial Nerve X)

Dr Jean Ayres introduced gravitational security, which refers to our ongoing sense of safety and stability within the gravitational field. This is a function of the fully myelinated vestibular nerve of the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII), which forms our vestibular sense. In conjunction with our proprioceptive and touch senses, it integrates all our senses and early movement patterns (reflexes), promoting the formation of synapses in higher cortical areas of our brain.

The combination of the vestibular with proprioception sense, visual and auditory senses is often called our Learning Triangle. It facilitates our first neuroplastic learning, ongoing posture alignment, movement, motor skills, future learning, emotional control, and executive functioning.

The vestibular system has a broad influence on the functioning structures of our nervous system:

1) Vestibular-spinal system, to and from the body, receives proprioception information.

It plays a crucial role in facilitating the “fight and flight” sympathetic mobilisation circuits of our Autonomic Nervous System (ANS).

2) Vestibular-cochlea CNIII. The vestibular apparatus in the inner ear controls balance and head orientation, while the cochlea apparatus controls auditory / hearing.

PVT also emphasises the role of the acoustic transfer function of middle ear structures and their ability to dampen acoustic frequencies outside the band associated with vocalisations of the human voice. It is within this frequency band that social communication, connection, and co-regulation occur.

3) Vestibular‐ocular reflex arc: CN III, IV, and VI vision and control eye movements by allowing eyes to fix on a moving object while staying in focus.

In combination with the above 1 & 2, Vestibular-proprioception, Auditory and vision, this is often called our learning triangle as these structures facilitate ongoing executive functioning and learning.

4) Vestibular‐cerebellum: regulation and modification of motor output based on signals received and matched to cortical intent. Along with input from the visual, auditory and spinal proprioceptive systems (above 3), results in fluid, smooth, accurate movement, posture, and balance.

The pioneering work of Dr Jeremy Schmahmann also indicates that dysfunction of the vestibular-cerebellar system can cause us to lose not only our physical balance but also our emotional equilibrium, our ability to learn new skills, regulate emotion, and sustain focus.

5) Accessory pathway: The XIth accessory cranial nerve, which innervates the trapezius and sternomastoid neck muscles, keeps the head upright despite changes in body position.

6) Reticular activating system RAS: Through connections to the reticular activating system and to the hypothalamus, thalamus, and Cortex with the regulation of behaviour, the arousal, sleep and awake cycles, attention, and sense of self, place, sense of safety and consciousness.

Links from the vestibular to the reticular system are essential in the bodily experience of disorientation, levels of arousal, and associated anxiety. This is because the descending reticular formation relays impulses from the hypothalamus to target organs of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), affecting heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, acid production in the stomach, etc. These systems are innervated below the level of conscious control.

The vestibular sense supports Bonding, Co-regulation and Self-regulation

At birth, an infant’s ANS function is immature, with only the protective responses of fight, flight, and freeze available. Due to the incomplete myelination of the ventral vagus branch (cranial nerve X), neuroception and connection regulation responses are underdeveloped. The bonding from primary caregivers, supported by the fully myelinated vestibular system, provides the safety to facilitate the myelination process of the ventral vagus nerves. This allows the maturity of the face-heart connection, vagal brake, gravitational security, and face-heart gut. The initial bonding allows co-regulation with others, learning self-regulation, and social engagement.

These very important early neurodevelopmental processes allow the maturation of neuroception and connection responses, enabling the full spectrum of nervous system regulation and executive functioning. Well-developed neuroception and myelinated ventral vagus are pivotal for our nervous system’s ongoing regulation and functioning.

Nervous System Dysregulation – Ontogeny & Survival Adaptions

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and developmental trauma are a subset of C-PTSD and lead to the development of subconscious survival adaptation strategies. While these adaptations are essential for coping during childhood, they can significantly impact our physical health and influence our ontology (way of being), including our connection with our soul values, behaviour, relationships, and happiness, hindering potential and success in later life. Many psychological approaches are top-down methods of trying to lessen the effect of these survival adaptations.

Polyvagal Theory (PVT) explains how ACEs and trauma events are embodied and embedded in our nervous system, severely impacting its maturation, development, and functioning.

ACEs also occur during the crucial period when our social engagement system is still maturing and could leave us with compromised neuroception and autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulation, prone to reactive protective regulation and our ontology (who we are) influenced by adaptive survival styles rather than our soul values – therefore prone to dysregulation.

Chronic stress and complex trauma events, leading to C-PTSD in our teenage years and adulthood, could also cause a previously well-developed nervous system to become disintegrated, with compromised neuroception and ANS regulation prone to protective reactions, with behavioural responses locked into adaptive survival styles (our ontogeny) and eventually dysregulated.

A dysregulated nervous system malfunctions at a regressed protection/survival level with limited access to the phylogenetically evolved thriving/social engagement level of safety, connection, and regulation. It is under the “control” of our survival adaptations rather than our free will and soul values.

A regulated unified Polyvagal nervous system enables our potential

PVT, combined with sensory processing theory, provides a unified Polyvagal framework to normalise neuroception and our ANS regulations – it aligns with their natural development and functioning. This is crucial to supporting our ongoing co-regulation, self-regulation, success, well-being and health.

Utilising the concept of neuroplasticity, awareness, and the will to change as essential ingredients to transformation and growth, PVT provides bottom-up ways to befriend our nervous system to support our health, well-being and potential from being realised. Combining this with top-down awareness approaches of our ontology (way of doing, being, becoming and belonging), we can move towards a life motivated by our soul values and not governed by our survival adaptations.

The enhanced PVT understanding greatly impacts how we structure, organise, and finance solutions to address chronic conditions. Instead of treatment, it highlights ongoing regulation alongside treatment, moving from the mindset of restoring health to ongoing maintenance and improvement of health and performance.

Health and wellness are not the absence of illness but our ability to continuously support our nervous systems in regulating our physicality and psychology and for us to live according to our soul values instead of being hindered by our Ontogeny.

At Neuroceptive Learning, Instead of treating chronic stress conditions as “disorders”, we provide services focusing on regulation alongside traditional treatment options. By normalising the nervous system to function at its phylogenetically evolved thriving level rather than at a regressed survival level, we strengthen the critical elements of safety, connection, and regulation, allowing trust, ongoing co-and self-regulation, societal interaction, fulfilment of potential, and psychological safety.

Summary of Regulated and Dysregulated Nervous System

A Regulated Nervous system supports you

Optimal Neuroception = Mostly safe evaluation in Connection responses of: Safe Sympathetic, Ventral & Safe Dorsal, Participate, Social Engagement, Restore

Behaviour: Considered response using language efficiently.

Connection: Coregulation with others & Self-regulation enables learning.

Executive function is influenced by the Prefrontal Cortex: (Thinking)

Motivated by: Values and Higher Purpose.

Ontology: Psychologically safe: belong to a group, speak up, set boundaries, contribute and challenge.

Psychology: Able to interact, function and thrive in the world.

Physiology: Optimal health regulation allows for feeling well enough to function daily. Happy hormones Oxytocin.

Moods: Participation, Curiosity and Wonder, Acceptance.

Result: Our unique talents / potential shine through.

A Dysregulated Nervous system hinders you

Bias Neuroception = Mostly unsafe evaluation in Protection reactions of: Sympathetic, Dorsal, Fight, Flight, Freeze, Fawn & Appease

Behaviour: Escalative reactions: too much (hyper), too little (hypo).

Connection: Compromised Coregulation & self-regulation & learning.

Executive function. The brainstem / sensory processing with compromised input from the Prefrontal cortex (Thinking) is in charge.

Driven by: Ontogeny/Survival adaptations: Anxiety, fear and emotions.

Ontology: Psychologically unsafe: feeling excluded, unable to speak up and set boundaries, afraid to contribute and challenge.

Psychology: Compromised ability to interact, function and thrive.

Physiology: Compromised health affecting daily functioning, e.g. sleep patterns, respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, metabolic, hormonal, reproductive and immune systems. Primarily stress hormones cortisol.

Moods: Resentment, Anxiety, Resignation.

Result: Our unique talents/potential are blocked.