From surviving to thriving

-

Introduction

In my Psychosynthesis Master’s thesis, I explored psychological safety in our current VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity) and BANI (Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, Incomprehensible) zeitgeist. A psychologically safe environment is one where individuals feel included and can speak up, contribute, and challenge their groups.

VUCA and BANI describe a world rife with stress and instability, significantly impacting our physical and psychological well-being. This has resulted in PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) and C-PTSD (Complex PTSD) being included in the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11, 2022) as “Disorders Specifically Associated with Stress.”

PTSD typically stems from acute, single-event trauma and has been recognised as a disorder since the 1980s. C-PTSD is linked to prolonged, chronic stress, often within relational contexts, and is now, for the first time, included in the ICD-11-2022. This distinction underscores modern stressors’ chronic, relational nature in our prevailing VUCA world.

-

Paradigm Shift: From Treatment to Regulation

Our societal structures – leadership, education, medical, and social – have yet to fully adapt to today’s rapidly evolving environment, where chronic stress is pervasive. This realisation calls for a paradigm shift from focusing on treating acute conditions to managing both acute and chronic conditions, emphasising regulation alongside treatment options.

This shift involves our leaders and systems embracing more systemic approaches that foster psychological safety, connection, regulation, and well-being, moving beyond merely treating symptoms to maintaining homeostasis and harmony between the individual and their environment.

Combining the insights and wisdom from different disciplines with the enhanced understanding of our nervous system provided by the Polyvagal Theory, we can find more suitable multidisciplinary management-regulatory approaches to offer psychological safety within today’s VUCA/BANI world.

-

The Polyvagal Unified Nervous System: A Phylogenetic Blueprint

Our nervous system is central to our health and well-being. It influences the regulation of our physiology, perception of reality, behavioural responses, capacity for connection, and relationships with others and the external world.

The prevalent understanding is that our Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) operates outside of conscious awareness, regulating our physiological state to ensure survival, while our central nervous system (our brain) is responsible for our conscious executive functioning.

Stephen Porges introduced the Polyvagal Theory (PVT), which enhances our understanding of the peripheral and central nervous systems as unified and provides a new evolutionary blueprint for their function. This unified polyvagal nervous system regulates our physiology and influences our psychology and behavioural responses. It ensures survival through protection regulation and enables us to thrive through connection regulation with ourselves, others, and our environment.

PVT indicates an evolved triune ANS regulation system instead of our traditional empirical stress and relaxation regulation. In addition to sympathetic fight-or-flight protection regulation, the dorsal vagal system’s shutdown provides a freeze immobilisation response. This creates three regulatory circuits: two protection circuits of fight-or-flight and freeze, and a connecting circuit facilitated by the ventral vagus complex, promoting social engagement and connection, also called the Face-Heart Connection.

PVT emphasises the interconnectedness of sensory processing, neuroception (subconscious evaluation of sensory information for safety), regulation, and executive functioning. This understanding reveals the bottom-up functioning of our nervous system: “I sense, I neurocept, I regulate, therefore I respond.” It shifts the focus from the traditional top-down cognitive functions of the central nervous system to the importance of sensory and regulatory functions in maintaining health.

When our neuroception evaluates sensory input as safe, the nervous system regulates for optimal health, and our ontology (who we are) supports connection behaviour, allowing us to experience psychological safety in our environments. But when our neuroception evaluates it as unsafe, our regulation prioritises protection above health, and our ontology results in protective behaviours – either overreacting or underreacting to stimuli – and we experience psychological unsafety in our environments. Our nervous system has evolved to operate primarily in connection regulation, resorting to protection regulation only in cases of real danger.

PTSD and C-PTSD often result in neuroception evaluations of unsafety due to real threats in our environments. Ideally, our neuroception should remain flexible to return to a safe evaluation when the danger has passed. This should happen when a single shock event results in PTSD. However, if there is prolonged, chronic stress in the environment, as in the case of C-PTSD, the neuroception evaluation may remain in an unsafe mode. This inflexibility can cause our neuroception to become biased towards unsafe evaluations, prioritising protection regulation of fight-or-flight and freeze above connection regulation, even when there is no real danger, leading to nervous system dysregulation.

There is also a progression in protection regulation, starting with fight-or-flight mobilisation and then moving into shutdown freeze immobilisation responses. The return to connection regulation occurs in reverse, from freeze to fight-or-flight to social engagement. However, a dysregulated nervous system is often stuck in freeze, an in-between freeze and fight-or-flight state, or a persistent fight-or-flight state. This in-between state is often the most difficult to overcome, requiring an already depleted system to become energised. Therefore, a dysregulated nervous system manifests in many different symptoms, depending on where the “stuckness” occurs.

So we have a chicken-and-egg situation: which came first—the disorder or the history causing our symptoms? Regardless, the symptoms of C-PTSD and even PTSD are similar to those of a dysregulated nervous system, manifesting in various chronic physical and behavioural conditions.

-

Psychology: The Influence of Our Subconscious Ontogenetic History

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are a subset of C-PTSD and lead to the development of subconscious survival adaptation strategies. While these adaptations are essential for coping during childhood, they can significantly impact our physical health and influence our ontology (way of being), including our behaviour, relationships, and happiness, hindering potential and success in later life.

Freud called these survival adaptations our ego structures and saw them as disorders of the mind. He used top-down psychoanalytic therapy to address these ailments of our unconscious mind.

4.1 Somatic Psychologies

Wilhelm Reich, the father of somatic psychologies, postulated that these adaptive patterns are embodied in our posture, naming them character styles, and treated them with intensive bodywork. Modern somatic therapies have evolved into more awareness-based energetic neuro-somatic bodywork therapies, as explained by Steven Kessler in The Five Personality Types.

The Polyvagal Theory further expands upon these modern somatic therapies and explains how ACEs are embodied and embedded in our nervous system as part of the sensory information we receive from our interoceptive, proprioceptive, and vestibular internal senses, as well as external senses of vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste.

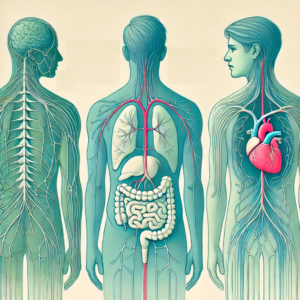

PVT highlights the importance of spinal nerves and the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) in transporting information to and from our brains. Furthermore, 80% of the fibres of the vagus nerve are sensory (from the body to the brain), and only 20% are motor (from the brain to the body), indicating the importance of bottom-up sensory approaches.

Our face-heart connection and vagal brake, facilitated by our ventral vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), combined with other vagal-complex cranial nerves (V, VII, IX, XI), enable the down-regulation of protective survival responses, allowing closeness, trust, societal living, and connection. Our face-heart-gut connection, facilitated by the dorsal branches of the vagus nerve, links to our digestion and freeze-protection response.

PVT also emphasises the role of our spinal nerves in facilitating our fight-or-flight protection response. When PVT is combined with Feldenkrais’s movement therapy, Jean Ayres’s sensory integration, and other reflex integration therapies, we learn the importance of gravitational security. Our vestibular system, cerebellum, and cranial nerve VIII facilitate our experience of safety within gravity and promote physical movement, emotional regulation, cognitive learning, and executive functioning.

At birth, an infant’s autonomic nervous system (ANS) function is immature, with only the protective responses of fight, flight, and freeze available. Due to the incomplete myelination of the ventral vagus branch (cranial nerve X), neuroception and connection regulation responses are underdeveloped. The bonding from primary caregivers, supported by the fully myelinated vestibular system, provides the safety to facilitate the myelination process of the Ventral Vegas nerves, enabling neuroception and future co-regulation with others, learning self-regulation, and social engagement.

ACEs experienced during this crucial time could hinder neurodevelopmental processes and leave us with compromised neuroception and autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulation, prone to reactive protective regulation. Therefore prone to dysregulation

Our face-heart-gut connection, face-heart connection, vagal brake, gravitational security, and sensory processing are all building blocks influenced by our ontogenetic history. The sensory information within these influences our neuroception evaluation, thus the nervous system’s regulation, our ontology (way of being), and our experience of psychological safety.

4.2 Transpersonal Psychosynthesis and the Paradoxical Theory of Change

Psychosynthesis, a transpersonal psychology developed by Roberto Assagioli, expands on traditional psychoanalysis and somatic psychologies by incorporating our will and soul/spirit as integral parts of our being alongside our body, emotions, and mind.

Assagioli drew from many modalities to expand on our ontology. He maintained that our psyche is more than our subpersonalities, body, mind, and emotions; we also have a soul or true Self that connects us to universal consciousness. His famous quote is, “We are not only a basement, but a whole house.”

Psychosynthesis focuses on aligning our will (what motivates and drives us) with our true Self (our soul) rather than allowing it to be governed by our survival adaptation patterns/subpersonalities formed in response to ACEs and trauma.

What drives and motivates us depends on whether our will serves our true Self or our subpersonalities.

Over the years, Psychosynthesis has also incorporated principles of other psychologies, such as systemic, Gestalt, and Arnold Beisser’s Paradoxical Theory of Change, which states that “Change happens when a person becomes what they are.”

Psychosynthesis, therefore, sees transformation as a combination of “a goal to change” and “awareness of different facets of our ontology or way of being”: our doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Our goal or our will to change is either governed by fear and survival patterns of our past or motivated by our true Self and the values of our soul.

Life is, therefore, a series of polarities encapsulated in the main polarity of the movement towards universal consciousness and the true Self, and the movement towards our earthly existence and subpersonalities – evolution and involution.

Transformation occurs through awareness of our will, ontology, ontogeny, and movement between these polarities.

4.3 Modern Interdisciplinary Approaches and Post-Traumatic Growth

Modern Psychosynthesis extends beyond therapy into personal development, executive leadership, and coaching. Renowned executive coach Sir John Whitmore, a pioneer in workplace coaching and co-creator of the GROW model, integrated Psychosynthesis into his approach to leadership coaching. In his book Coaching for Performance, Whitmore emphasised reframing life as a developmental journey, seeing obstacles as opportunities for growth, and recognising the importance of aligning with one’s higher purpose. He introduces the concept of post-traumatic growth – the positive psychological change that can occur after a life crisis or traumatic event.

Roger Evans, co-founder of the Psychosynthesis Institute and author of The Five Dimensions of Leadership (2019), further synthesised this into five critical dimensions of leadership:

- Self-awareness

- Awareness of the other

- Awareness of the system

- Individual will and freedom to choose and act

- Vulnerability: The ability to ask for help and show vulnerability as a leader.

Vulnerability is also at the heart of PVT; our neuroception evaluates whether we can trust and be near others. It allows for the down-regulation of protective reactions to enable connection responses and psychological safety. When we have healthy neuroception and are regulated, we connect to the Self – our values and universal consciousness. Our will can be free to choose, and we have agency – we have self-leadership.

From a PVT perspective, a regulated nervous system supports and enables the five dimensions of leadership. Thus, real leadership starts with self-leadership and providing psychologically safe environments in which group members’ self-leadership can unfold.

In the last 30 years, many progressive therapies have incorporated the PVT understanding of our nervous system. They are starting to provide ongoing solutions for finding psychological safety within our VUCA world. Two such approaches are Dr. Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing method and Dr. Laurence Heller’s NeuroAffective Relational Model (NARM).

NARM is a transformative method designed to integrate complex trauma or C-PTSD resulting from ACEs. It integrates top-down psychotherapy and bottom-up somatic approaches within a relational context, drawing from psychodynamic psychotherapy, attachment theory, Gestalt therapy, and somatic psychotherapy approaches. It acknowledges that we are more than our trauma and promotes post-traumatic growth, finding our true Selves amidst our survival strategies and our route back to connection with Self, others, environment, and global consciousness or Spirit.

PVT also explains why many methods incorporating ancient Eastern traditions, such as Polarity and Sophrology, effectively provide ongoing regulatory solutions. They restore the flow of our life energy or, in PVT terms, normalise our neuroception and ANS regulation.

-

PVT Combined with Interdisciplinary Approaches: An Updated Blueprint

Combining Polyvagal Theory with other interdisciplinary approaches offers a more comprehensive framework – a phylogenetic blueprint – for understanding our humanity, physical and mental health, well-being, and leadership in today’s VUCA world.

Our nervous system functions from the bottom up: from the body to the brain and within the brain, from the subconscious (brainstem) to the conscious (thinking prefrontal cortex). In between, neuroception occurs, subconsciously evaluating sensory information and influencing how our nervous system regulates our health and our ontology: who we are, whether we are motivated by our concerns or our soul values, and how this influences our experience of psychological safety in the world.

Thus, we can use a phylogenetic understanding of the functioning of our nervous system to address the effects of our ontogeny (our embedded history) on its regulation, our ontology (way of being), and our experience of psychological safety in the world.

This phylogenetic understanding can also be extended into the broader systemic societal context. Thus it also provides a blueprint to guide leaders in providing psychologically safe environments and structures – locally, nationally, or globally – that allow the unfolding of individual self-leadership and change from the inside out. These environments enable collaboration and joint responsibility for health and well-being through interdisciplinary approaches:

- Aligned with PVT’s understanding of our unified nervous system, which regulates our physical and psychological health for protection and connection.

- Aligned with the natural development and functioning of our nervous system, both bottom-up and top-down approaches are appropriate.

- Emphasising the individual as a holistic system within larger systems and environments, with constant regulation, connection, and safety within and between.

- Safety: Neuroception (inner safety) leads to psychological safety (external safety).

- Connection: Self (inner wisdom of our soul) to others, family, groups, society, world, universe (external).

- Regulation: Nervous system regulation (inner) combined with co-regulation and continuous self-regulation learning (external world).

- Acknowledging our spiritual nature, purpose, and connection to universal consciousness.

- Acknowledging our will as a motivator and being in service of our Self.

- Aligned with how we naturally learn and transform: through a goal and awareness.

- Allowing for the polarities of two extremes with a neutral centre and endless possibilities in between—triune AND/OR regulatory solutions to manage both acute and chronic conditions, emphasising regulation and treatment.

Whilst we cannot escape our VUCA/BANI world, leaders can foster collaborative, consistent change and regulation by supporting individual self-leadership and providing structures aligned with our phylogenetic framework of continuous regulation with our environment.

Health is not merely the absence of illness but our ability to feel safe, connect, regulate, and live according to the core values of our true Self.

-

Neuroceptive Learning: Post-Traumatic Growth

At Neuroceptive Learning, we realise that stress is a reality of our time – we cannot escape our VUCA world. Still, we can learn self-leadership to regulate and be more in harmony with others, our environment, world, and universe. We can learn how to experience our world as psychologically safe in the broader VUCA/BANI context.

Therefore, we focus on optimising nervous system regulation rather than merely treating symptoms. Our approach combines Polyvagal Theory, Psychosynthesis, and other modalities to help individuals restore balance and achieve psychological safety.

This method empowers individuals to live according to their true values and higher purpose, fostering resilience and well-being in a complex world. It promotes self-leadership and post-traumatic growth.